Speaking at Stanford University on Monday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had an improbable request for Iran’s revolutionary Islamist government.

“We just want Iran to behave like a normal nation,” he said. “Just be like Norway,” he added wryly, drawing laughs from the crowd.

But as Pompeo and other Trump administration officials know full well, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the generals who guard his power in Tehran will never shape their foreign policy to the United States’ liking. What Pompeo implied was less a change in Iran’s behavior than a change in its leadership.

President Donald Trump and his senior officials insist they do not seek regime change in a military sense. But they clearly would not mind seeing their campaign of maximum pressure against Iran, now reinforced by the killing of its most valued military leader, result in a drastic upheaval — and possibly even fall — of Iran’s theocratic government.

“We support the Iranian people and their courageous struggle for freedom,” Trump said at a rally Tuesday night in Milwaukee, referring to recent antigovernment protests in the country.

His approach is a contrast to the one pursued for years by the United States during the Obama administration, which, along with Europe, tested the possibility that Iran could be coaxed, not pressured, into a new era.

While it was not a stated goal of the 2015 nuclear deal with Tehran, many Obama administration officials believed it could lead to an opening of the country’s economy and provide a lift to moderate reformers who might gradually steer Iran onto a more benign path — and perhaps, one day, to an altogether different kind of government

In a Nowruz message to Iranians in March 2015, President Barack Obama urged them to adopt the nuclear deal and choose “a better path — the path of greater opportunities for the Iranian people.” That included “more trade and ties with the world,” he continued, along with “foreign investment and jobs,” “cultural exchanges,” foreign travel and “a brighter future for you — the Iranian people, who, as heirs to a great civilization, have so much to give to the world.”

When Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, in other words, he didn’t just shred an international agreement. He also turned his back on a big idea about how a rogue nation might be drawn into peaceful coexistence with the West.

Conservatives called Obama’s vision doomed from the start, and have argued that the relief from economic sanctions Iran won in exchange for limits on its nuclear program only funded more Iranian aggression in the Middle East and beyond.

Nor did Iranian politics show much sign of moderating, despite conciliatory talk from Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani and its U.S.-educated foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif. Now the Trump administration is testing an alternate approach, having abandoned the nuclear deal and adopted its “maximum pressure” posture.

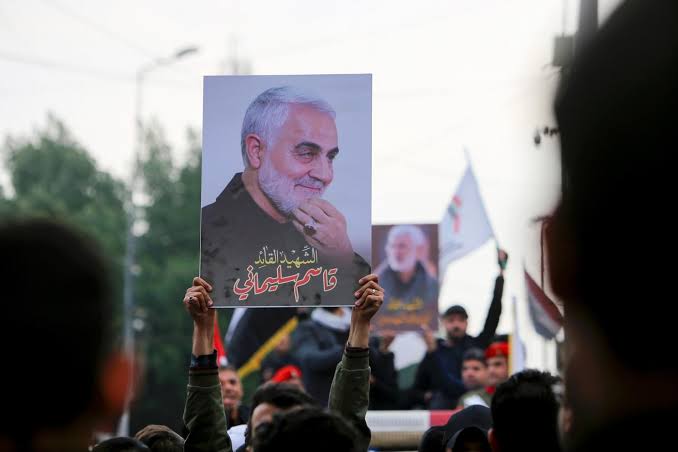

Administration officials are especially bullish about that strategy in recent days, as Iran’s government contends with renewed protests and absorbs the killing of Gen. Qassem Soleimani. And in an ominous turn for Tehran this week, Britain, France and Germany formally accused Iran of violating the 2015 nuclear deal, after months of effectively looking the other way at increased Iranian nuclear activity.

“In neither case was the ultimate, explicit goal ‘regime change,’ ” said Suzanne Maloney, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former State Department official in the George W. Bush administration.

“But there was a kind of theory of the case under Obama that engagement could lead to the sort of fundamental changes in Iranian policy, almost irrespective of the character of the regime, that the U.S. had been seeking since 1979,” she said.

No one expected overnight change, but many Obama officials believed that Secretary of State John Kerry’s copious diplomacy with Zarif, fueled by economic integration, might be the beginning of a deeper relationship that could defuse Ayatollah Khamenei’s declarations that Iran could never trust America.

The administration’s current approach “contrasts in an almost perfectly polarized fashion” with Obama’s, Maloney said. That strategy, which began with Trump’s May 2018 abandonment of the nuclear deal and was followed by punishing sanctions on Iran’s financial system and oil exports, “rests on the idea that Iran only responds to really tough pressure.”

Maloney and other analysts say that, like Obama’s effort at outreach, Trump’s strangulation approach may also be stymied by an Iranian government that has resisted 40 years of alternating U.S. efforts to reshape or replace it.

Iran grappled with popular protests months before Trump exited the nuclear deal and began turning the screws against its economy. And its interventions in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen continue largely unabated.

But in recent days, a chorus of Trump administration officials has boasted that the strike against Soleimani and subsequent military threats are “re-establishing deterrence” against Iranian aggression, even if some privately admit that Trump’s own reluctance to use military force was part of the problem.

And they seem increasingly triumphal about the signs of stress on Iran’s government, now facing the third round of mass demonstrations in the country since late 2017 — this time prompted by its military’s downing of a civilian airliner over Tehran. Recently, Trump has issued several tweets in support of the protesters, including a few in Persian.

“We think the regime is in real trouble,” Robert C. O’Brien, the president’s national security adviser, told NBC News on Sunday. Trump’s special envoy for Iran, Brian H. Hook, recently boasted that Tehran’s clerical government faces “its worst political unrest in its 40-year history.”

Trump’s former national security adviser, John R. Bolton, chimed in Sunday, tweeting: “The Khamenei regime has never been under more stress. Regime change is in the air.”

Trump and his top officials insist that is not their goal — especially not through the use of force. “We do not seek war, we do not seek nation-building, we do not seek regime change,” the president said in remarks this month.

It is clear, however, that administration officials hope to undermine the Iranian government. Early in Trump’s presidency, a memo that circulated in his White House written by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a hawkish Washington think tank, suggested “a strategy of coerced democratization” for Iran.

“The reality is that Iran’s regional behavior is not going to meaningfully change until at a minimum there is a different supreme leader, and perhaps not even until there is a different government altogether in Tehran,” said Karim Sadjadpour, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Ayatollah Khamenei is 80, but his successor will be chosen by a conservative clerical body. Iran does hold ostensibly democratic elections for its presidency, but the ayatollah can handpick candidates, and recent elections have been marred by fraud.

In the meantime, few analysts believe that recurring protests portend another Iranian revolution. Ali Vaez, the Iran project director at the International Crisis Group, said the government’s crackdown on demonstrations last fall showed its fierce determination to retain power. But he added, “The Trump administration got the opposite message, which is that the maximum pressure campaign is working.”

He also questioned Pompeo’s assertion that the killing of Soleimani had restored “deterrence” against aggression by Iran, citing its missile attacks last week on bases in Iraq where U.S. troops are stationed.

“If firing missiles into bases housing U.S. soldiers is ‘restoring deterrence,’ I don’t know what the word means anymore,” Vaez said.

But as Trump moves into the next stage of his showdown with Iran, one question is whether his impulsive approach could abruptly shift.

Paul Salem, the president of the Middle East Institute, noted that Trump’s Iran policy had been shaped by hawkish officials, including Pompeo, Hook and, until his departure in September, Bolton.

Those officials believe “that the Islamic republic is beyond hope and that the options are to weaken it or let it collapse, and they are not interested in giving it a deal,” he said.

But Salem added, “I don’t think that’s what Mr. Trump wants.” The president loves a grand bargain, and repeatedly says he is open to a deal with Tehran.

Last week, Trump said that such a deal could allow Iran “to thrive and prosper, and take advantage of its enormous untapped potential. Iran can be a great country.”

In that moment, his vision sounded much like Obama’s — even if their approaches couldn’t be more different.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.