Nothing describes frustration than the tale of a banker who has to plead with his customer to choose their own terms on how they will repay a loan they have already defaulted on.

The shoe is usually on the other foot, with an overbearing lender deciding on how long you will stay with their money, what rate you will pay and setting up painful repercussions for missing payments that should whip you into line.

The famous quote, “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s the bank’s problem”, holds true until you are in Kenya in 2020.

Almost everyone who took out a real estate loan is defaulting, becoming the banks’ problem.

Bankers are unable to sell property on the auction market and have now been forced to renegotiate loans on their customers’ terms. A keen observer will have noticed that auctioneers are finding it hard to dispose of property, with the same assets appearing week after week in the papers.

“Customers discovered that banks cannot sell the properties and when banks approach them they tell them to go ahead and sell,” said Eric Oluoch, group CEO at debt management firm Quest.

“Banks realised they will find themselves holding a huge portfolio of property that cannot be disposed of and that is when they came up with this new plan. I think what we are going to have is that the terms of the mortgages are going to be longer,” he said.

Economist Robert Shaw says he does not pity banks for falling into this quagmire. He said lenders fuelled this unsustainable system and are victims of their own practices.

“It is not just a question of customers, banks also made lending decisions without being aware of the circumstances of the market. Banks must bear in mind that the relationship with a customer is two way, they should look at themselves and see that maybe there is a different way,” he said.

Mr Oluoch, says this is a build-up from when bankers never used to lend to people without property until Barclays started offering unsecured loans.

This ushered in a period where loans could be issued on the strength of a payslip, a balance sheet or even a history of banking transactions, liberalising the market and causing a credit boom.

During this period of plenty, a housing boom was created in the market funded partly by a thin mortgage sector but mostly unexplained cash.

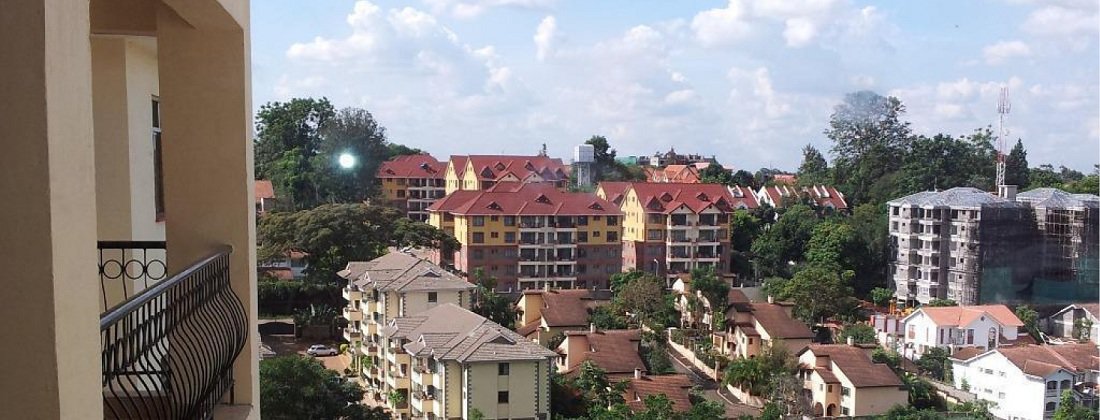

These houses were then used to take up more loans to build more for a seemingly insatiable market for office space and high-end properties in the Rundas and Kilimanis.

“At the time, a lot of people were putting up houses, which fuelled a situation of speculation in the real estate sector with superficial demand and crazy prices. You could go to an empty plot kilometres away from Nairobi and because a university had promised to build there or a road would be built there later, prices would go up,” Oluoch said.

“Banks were giving loans on properties with crazy values,” he said.

But when the rate cap was introduced, suddenly banks became defensive, stopped lending to risky businesses and concentrated on those with property, starving the rest of the economy of much needed cash to keep up the demand.

Then the economy took a dip with government delaying payments to suppliers and cutting down expenditure on large-scale infrastructure.

The domino effect hit businesses denied loans by banks and starved of cashflows by government, leading to losses in wider sectors of the economy.

As a reaction, businesses themselves started firing workers to cut costs, sending home thousands of employees, and demand for houses vanished.

People stopped servicing their loans and banks started foreclosures, repossessing houses and selling them via auction.

“With no disposable income, it became a case of whether you will eat and pay school fees or service a loan, it was a no-brainer,” Oluoch said.

The problem was that those who sit at auctions are looking for a bargain and would not pay those crazy values the market boom had created.

But repricing was almost impossible given the consumer protection laws stopping banks from selling distressed properties for peanuts, requiring them to get as much value as possible.

Section 97 of the Land Act 2012 requires banks to exercise duty of care on reposed properties and empowers defaulters to sue if their assets are sold off cheaply.

It came up after several cases of collusion had seen properties sold off for a song then banks would audaciously demand more money from auctioned clients to top up the difference.

“The problem is that nobody is offering 75 per cent so we keep advertising, but we are not selling. So someone is sitting on money, but can’t buy because the price is up,” said NCBA Group Managing Director John Gachora.

Houses that were selling for Sh25 million in Kilimani two or three years ago are going for Sh13 million and that is by their owners not the banks.

Deepak Dave of Riverside Advisors said the costs and agitation involved with repossession only to then find you are still in loss makes no sense.

According to bankers who have talked to Smart Company, they are now forced to go back to the property owners to renegotiate terms.

“The customer shows you these are my Local Purchasing Orders, and he has not been paid, at that point what can you do, we just sit with them and say look, let us see what arrangement we can have rather than auctioning,” a local banker, who did not wish to be named, told Smart Company.

National Bank of Kenya CEO Paul Russo says the first option of dealing with defaulters is not to auction but rather try and sit with them to find an amicable solution.

“There are those willing to come to the table, those we are going after their security and those who we are pursuing over and above through courts. You can’t rule out that there are people who take loans with no intention of repaying,” Russo said.

Deepak said the strategy only makes sense if the restructuring is done with enough cost attached or a recovery-dependent cash sweep that means the developer is not getting a gift.

He said that he hoped the Central Bank of Kenya is keeping an eye on what is being signed off at the banks

“I think what is happening is the defaulting developers are likely getting a gift. If the market recovers, then their debt looks less expensive. If it stays weak, then the lender is carrying the cost of waiting, not the developer,” he said.

There is fear that we may have blown a real estate balloon like the 2008 financial crisis and the reason it has not burst is this accounting trick.

Deepak said that fake restructuring is not repricing housing, it is falsely padding bank capital. Sooner or later this freezes working capital and capex in the economy, hurting the wananchi most of all as demand falls.

“The 2008 crisis did not affect us so much because we were not credit intense but now we have fintechs lending, banks setting up fintechs to lend and people are credit driven. Unfortunately for us it is driven by consumption rather than creating cash-flow. The government needs to find a way to pump money into the economy so that money starts flowing and hopefully people can start paying,” said Oluoch.

To survive, banks have stopped lending to real estate projects a trend that has seen mortgage banks chase mobile loans and retail banking rather than touch real estate.

“The prolonged troubles in the real estate sector, and the economy at large, have weakened banking asset quality. Based on banks internal models and expectations of the economic environment, this potentially leads to increased provisioning levels and write offs. Cautious lending by banks, in turn, leads to economic constraints as PSCG is subdued,” said Patrick Mumu, a research analyst Genghis Capital Ltdd

Last year HF Group cut prices on 700 houses by 30 per cent and this year decided it will exit the home-construction business once it completes the units it is currently building. Shelter Afrique, another mortgage lender, froze loans for two and a half years and announced restructuring and reforms of its financing model.

Bankers know that these attempts at surviving will not suffice and only removal of the law limiting pricing will help them realise the value of their dud home loans. Mr Gachora says the creation of a State-backed asset management company that will shoulder the difference between what potential buyers are demanding and the valuation of the distressed property could be the solution.

“If the buyer in the market takes at say 10 per cent below the required minimum price, government should take that hit and give a very long term loan to the owner of that asset to repay over time,” said Mr Gachora.

The real burden of these restructured loans is still unknown given the structures of loan agreements related to real estate that range from mortgages, loans secured by properties and real estate properties financed by banks.

According to Central Bank data, as of October last year, banks had lent Sh372.5 billion to the real estate sector.

About 17 per cent of Kenya Commercial Bank has been loaned out to real estate while Equity Bank has given 23 per cent of their book to housing loans. Cooperative Bank has packed 12 per cent of their loan book in housing.

Housing Finance, which primarily funds homes, has no indication of what percentage of their book is exposed to real estate.

Analysts say that we first need to get honest figures out of the banks and then get them to raise capital or write off the book.

Then later, an “asset recovery agency” to help banks monetise and liquidate their bad loans is now needed, and CBK should allow a local fund manager to set up such a fund.

“Second option is to help the banks hide the problem and ‘bless’ bad restructures so the banks can corruptly hide the issue, then we all pray the problem just solves itself. This would be highly risky not to mention unlikely, and I believe the governor is not the sort to let that happen,” Deepak said.

Mumu says all is not lost, the real estate market has experienced appreciation in certain pockets though this has been supported by infrastructure, not speculation.

Nation